The KED View

No holds barred: State support for Samsung, SK Hynix, Hyundai Motor

With the golden rules of fair play apparently down the drain, it won’t be easy to cry foul for heavy subsidies

By Jan 03, 2023 (Gmt+09:00)

4

Min read

Most Read

LG Chem to sell water filter business to Glenwood PE for $692 million

Kyobo Life poised to buy Japan’s SBI Group-owned savings bank

KT&G eyes overseas M&A after rejecting activist fund's offer

StockX in merger talks with Naver’s online reseller Kream

Mirae Asset to be named Korea Post’s core real estate fund operator

It couldn’t come at a worse time.

South Korea’s exports are set for a 4.5% decline in 2023. So believes the Yoon Suk-yeol government.

The gloomy outlook for Asia’s fourth-largest economy, where exports account for half its GDP, is all the more surprising as the projection comes from a government that tends to be optimistic and bullish, often dismissing the central bank’s downbeat prospects.

Whenever the Korean economy has gone into a downward spiral, it was exports that came to the rescue.

During the Asian foreign-exchange crisis in 1998, Korea’s exports fell by 2.8%. A year later, however, exports sprang back to an 8.6% rise, powered by domestic companies’ quick jump on the burgeoning information technology boom in the US and other advanced countries.

In 2009, when the global economy fell into a financial crisis, Korea’s exports plummeted 13.9% only to rebound to an increase of 28.3% the following year.

It has signed FTAs with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the European Union (EU), Peru and the US.

With India, Korea clinched the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) in 2009 to tap into one of the world’s most populous countries.

More recently, Korea’s exports declined 5.5% in 2020, gripped by the COVID-19 pandemic, but climbed 25.7% the next year, driven by new growth drivers such as bio-health and batteries, as well as the backbone industries of semiconductors, petrochemicals and cars.

TURNING CRISIS INTO OPPORTUNITY

Korean exporters, both big companies and smaller enterprises, are no strangers to turning crises into opportunities.

In 1974, when inflation was rampant due to the first oil shock, Samsung Electronics Co. acquired a near-bankrupt Korean chipmaker.

In the late 1980s Japanese companies, mired in recession, were reducing facility investment whereas Samsung started building new lines and emerged as the No. 1 DRAM maker.

Hyundai Motor Co. also took the bull by the horns. In an aggressive marketing effort in 2009, it unveiled an “assurance program” in the US market, under which the carmaker would buy the car back from the buyer if they lost their job within a year of their purchase. The strategy proved successful.

And in the Year of the Rabbit, challenges are daunting for big companies such as Samsung and Hyundai, let alone smaller firms.

It is no secret that Samsung, the world’s largest smartphone and memory chipmaker, is likely to see its semiconductor business slip into the red in the second quarter.

The never-ceasing faceoff between the US and China is posing a risk for Samsung and SK Hynix Inc. as China plus Hong Kong account for 60% of the chipmakers’ exports.

It is also unsettling to see Japan trying to reclaim its lost chipmaking glory while closing ranks with the US and Taiwan through business tie-ups.

In the face of the growing external uncertainties, Korean lawmakers, much to chipmakers’ chagrin, passed a bill last month that allows for 8% tax breaks on chipmaking facility investment.

ALL THAT FUSS

And then there came all that fuss.

Last week, the finance ministry said it plans to submit an amendment to the law to the National Assembly to hike tax incentives for chipmakers to at least 10% following President Yoon’s call for an extra tailwind.

The auto industry also has to face the music.

The biggest stumbling block for Korean carmakers’ exports to the US, one of their biggest markets, is the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which favors electric cars with batteries originating from the US or its free trade partners.

According to the new IRA guidelines announced on Dec. 29, cars acquired for use or lease by the taxpayer and not for resale are added to the list of "qualified commercial clean vehicles" for tax benefits.

However, the portion of such vehicles among exported Korean vehicles is insignificant.

In November, the Korean government and Hyundai Motor requested the US government give Korean carmakers a three-year grace period before applying the eco-friendly tax credit law to their electric cars sold in the US.

But chances are slim for the US to accept such a request.

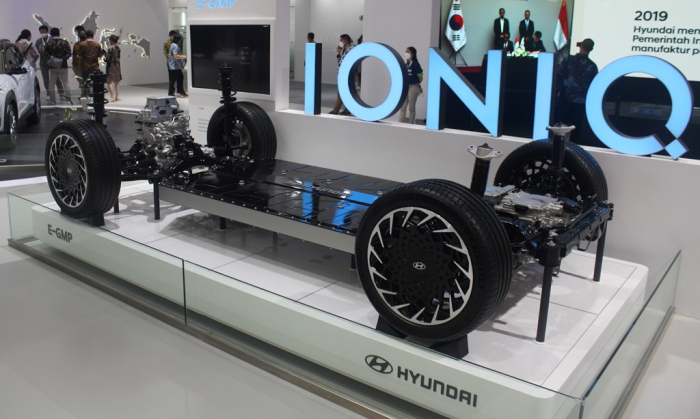

In October, Hyundai broke ground on a $5.54 billion electric vehicle and battery plant in the US state of Georgia. Still, the automaker has to bleed in its key market until the plant is up and running in the first half of 2025.

BATTLE FOR SUPREMACY

The battle for supremacy in the chip, EV and battery sectors is a war with no holds barred.

A struggle for the top place is often likened to a World Cup tournament where all-star players from each country are called in for an all-out fight.

Last year, Korea’s exports of semiconductors and cars and related auto parts reached $129.2 billion and $77.4 billion, respectively, accounting for 19% and 11% of the country’s total exports.

The stark reality is that chips and cars are the country’s breadwinners despite scant state support and subsidies, citing no preferential treatment for “chaebol,” or conglomerates in a pejorative sense.

With the US and other major economies offering huge subsidies for their own companies, the golden rules of fair play have apparently gone down the drain.

Even if subsidies are provided to Samsung, SK Hynix and Hyundai alongside unprecedented tax benefits, no one could easily take out a yellow card, crying foul.

Write to Keon-Ho Lee at leekh@hankyung.com

In-Soo Nam edited this article.

More to Read

-

Business & PoliticsKorea plans to raise tax breaks for chipmakers, key industries

Business & PoliticsKorea plans to raise tax breaks for chipmakers, key industriesDec 30, 2022 (Gmt+09:00)

2 Min read -

Electric vehiclesHyundai Motor to boost US presence with $5.5 bn new Georgia EV plant

Electric vehiclesHyundai Motor to boost US presence with $5.5 bn new Georgia EV plantOct 26, 2022 (Gmt+09:00)

3 Min read -

Korean chipmakersKorea may be backpedaling in semiconductor push: Lawmaker

Korean chipmakersKorea may be backpedaling in semiconductor push: LawmakerMay 20, 2022 (Gmt+09:00)

4 Min read -

The KED ViewCan Samsung Electronics ever catch up to foundry leader TSMC?

The KED ViewCan Samsung Electronics ever catch up to foundry leader TSMC?May 03, 2022 (Gmt+09:00)

4 Min read

Comment 0

LOG IN