Older Voters Are Taking Over in the World’s Wealthy Democracies

South Korea’s legislative election this week will offer an early glimpse at the collision between demographics and democracy

By The Wall Street Journal Apr 15, 2024 (Gmt+09:00)

LG Chem to sell water filter business to Glenwood PE for $692 million

KT&G eyes overseas M&A after rejecting activist fund's offer

Kyobo Life poised to buy Japan’s SBI Group-owned savings bank

StockX in merger talks with Naver’s online reseller Kream

Meritz backs half of ex-manager’s $210 mn hedge fund

SEOUL—On the surface, South Korea’s legislative election this week looks much like past votes. Candidates are holding rallies and parties are engaging in their usual mudslinging.

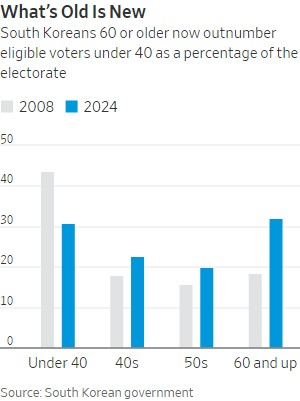

But there will be a new wrinkle when South Koreans head to the polls Wednesday: The number of eligible older voters, for the first time, will outnumber those under 40.

Roughly 32% of the electorate is 60 or older, vs. nearly 31% who are younger than 40, according to government data. That is a dramatic shift from 2008 when the total number of younger voters outnumbered seniors by a more than 2-to-1 margin.

The graying of electorates—and the officials who represent them—is becoming increasingly common in advanced economies, as people live longer and birthrates plunge. The world’s 10 largest countries by population now all have leaders older than 70.

The advancing age of voters has raised concerns that governments, backed by bigger blocs of seniors, will give priority to programs geared toward the elderly at the expense of public spending aimed at younger people. Some academics have called for overhauling how democratic governments are structured to ensure better representation for young and old.

Voters in many countries are aging, particularly among wealthy democracies. That will be on display in a major political year, when an estimated four billion people, or roughly half the world’s population, are participating in dozens of elections—from the U.S. to India to the U.K.

South Korea, home to the industrialized world’s lowest birthrate for the past decade, offers an early glimpse at the collision between demographics and democracy.

On Wednesday, the country votes on all 300 seats in its unicameral National Assembly. South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, who is limited by South Korean law to a single five-year term that ends in 2027, hopes his ruling conservatives regain majority control of the legislature. Older voters in South Korea skew to the political right, though polls show a tight race.

“I never thought low birthrates was a serious issue but suddenly I fear that I’ll be living in a society where political power and welfare benefits will all be dominated by the older generation,” said 31-year-old Lee Ji-ae, who said she is concerned about projections that South Korea’s national pension fund will run out of money by the time she retires.

Kim Cheol-yong, a 64-year-old retiree, said he thinks the problem is that younger people are less interested in politics and national security issues. He said many people his age were shocked to see young people supporting the former administration of left-leaning Moon Jae-in, who favored engagement with North Korea and is Yoon’s predecessor. Kim said he has always voted for conservatives, who favor tougher rhetoric with Pyongyang.

“We’re not ignoring the younger generation’s opinions,” he said.

South Korea has fewer young legislators than nearly every other country in the world, with about 4% of them 40 and under, placing it in 142nd place out of 147 nations, according to a report by the Inter-Parliamentary Union. In the U.S., which ranked slightly higher at 122, roughly 10% of legislators are under 40.

South Korea’s two major parties haven’t directed much of their campaigning toward younger citizens, despite their potential allure as swing voters. Younger voters have recently shown more allegiance to individual policies than partisanship, said Heo Jin-jae, of Gallup Korea, who researches public opinion.

Younger voters in the U.S. are also experiencing a disconnect with their representatives. The two major presidential candidates in November’s elections—81-year-old President Biden and 77-year-old Donald Trump—are decades older than them. The median age of U.S. senators is 65.

On Monday, Biden proposed slashing student debt for nearly 30 million Americans, a move that aimed in part at appealing to young voters. But the effort is likely to face challenges from Republicans.

Millennials and Gen-Z voters will represent 48.5% of the eligible electorate this fall, according to census data analyzed by researchers Mike Hais and Morley Winograd.

“If you look at what Congress has done in this world, they continue to spend, reinforce and help programs for senior citizens at the expense of doing something dramatic for younger people,” said Winograd, who, with Hais, has written three books on millennials and politics. Younger Americans show more interest in third parties or abstaining from voting, they said.

The world has never before witnessed a moment where older people have begun outnumbering younger ones, meaning many democracies are becoming “gerontocracies,” said Yosuke Buchmeier, a research associate at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, who recently co-wrote a paper called, “The Aging Democracy.” With elected officials already much older than the population average in many countries, younger voters globally have become disenfranchised, apathetic and underrepresented in legislatures, he said.

The very notion of “one person, one vote” in democratic political systems may need to be rethought as seniors come to dominate voting bases, he added. Proposals range from offering young parents extra votes for their children to establishing a “generational election system,” in which each age bracket gets a confined number of legislators to ensure population-wide representation.

“We will see more aging democracies in the future,” Buchmeier said. “The question is who is democracy for and how can democracy really reform itself?”

Older people don’t necessarily vote along generational lines, since they often have children and grandchildren. They also don’t generally switch political ideologies as they age, said Sarah Harper, a gerontology professor at the University of Oxford. “You don’t suddenly wake up, you’re 50 and you’re right wing—that’s not how it works,” Harper said.

The number of seniors, relative to working-age individuals, will double in wealthy economies over the next several decades—and will drag on global growth from 2040 onward, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Paying for soaring public debt for pensions, healthcare and other services could spur intergenerational inequalities, too, the OECD said.

Lee Soon-ja, 62, said she doesn’t think older voters outnumbering younger ones is a good sign for South Korean society. She fears young people will feel they have less of a voice in politics.

“I hear that young people are already less interested in politics and voting than we are,” Lee said. “But if they start to feel that we make all the political decisions, I fear it will create misunderstandings with our children and grandchildren’s generations.”

Write to Timothy W Martin and Dasl Yoon at Timothy.Martin@wsj.com

and dasl.yoon@wsj.com

-

-

EconomySouth Korea to boost aid for chipmakers to $23 billion, expanding extra budget

EconomySouth Korea to boost aid for chipmakers to $23 billion, expanding extra budgetApr 16, 2025 (Gmt+09:00)

-

AutomobilesSouth Korea announces emergency support for auto sector against US tariffs

AutomobilesSouth Korea announces emergency support for auto sector against US tariffsApr 09, 2025 (Gmt+09:00)

-

EconomyChina says it is aiming to coordinate tariff response with Japan, South Korea

EconomyChina says it is aiming to coordinate tariff response with Japan, South KoreaApr 02, 2025 (Gmt+09:00)

-